To tax (from the Latin taxo; "I estimate") is to impose a financial charge or other levy upon a taxpayer (an individual or legal entity) by a state or the functional equivalent of a state such that failure to pay is punishable by law.

Taxes are also imposed by many subnational entities. Taxes consist of direct tax or indirect tax, and may be paid in money or as its labour equivalent (often but not always unpaid labour). A tax may be defined as a "pecuniary burden laid upon individuals or property owners to support the government […] a payment exacted by legislative authority." A tax "is not a voluntary payment or donation, but an enforced contribution, exacted pursuant to legislative authority" and is "any contribution imposed by government […] whether under the name of toll, tribute, tallage, gabel, impost, duty, custom, excise, subsidy, aid, supply, or other name."

The legal definition and the economic definition of taxes differ in that economists do not consider many transfers to governments to be taxes. For example, some transfers to the public sector are comparable to prices. Examples include tuition at public universities and fees for utilities provided by local governments. Governments also obtain resources by creating money (e.g., printing bills and minting coins), through voluntary gifts (e.g., contributions to public universities and museums), by imposing penalties (e.g., traffic fines), by borrowing, and by confiscating wealth. From the view of economists, a tax is a non-penal, yet compulsory transfer of resources from the private to the public sector levied on a basis of predetermined criteria and without reference to specific benefit received.

In modern taxation systems, taxes are levied in money; but, in-kind and corvée taxation are characteristic of traditional or pre-capitalist states and their functional equivalents. The method of taxation and the government expenditure of taxes raised is often highly debated in politics and economics. Tax collection is performed by a government agency such as Canada Revenue Agency, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) in the United States, or Her Majesty's Revenue and Customs (HMRC) in the UK. When taxes are not fully paid, civil penalties (such as fines or forfeiture) or criminal penalties (such as incarceration) may be imposed on the non-paying entity or individual.

Taxation has four main purposes or effects: Revenue, Redistribution, Repricing, and Representation.[citation needed]

- The main purpose is revenue: taxes raise money to spend on armies, roads, schools and hospitals, and on more indirect government functions like market regulation or legal systems.

- A second is redistribution. Normally, this means transferring wealth from the richer sections of society to poorer sections.

- A third purpose of taxation is repricing. Taxes are levied to address externalities; for example, tobacco is taxed to discourage smoking, and a carbon tax discourages use of carbon-based fuels.

- A fourth, consequential effect of taxation in its historical setting has been representation. The American revolutionary slogan "no taxation without representation" implied this: rulers tax citizens, and citizens demand accountability from their rulers as the other part of this bargain. Studies have shown that direct taxation (such as income taxes) generates the greatest degree of accountability and better governance, while indirect taxation tends to have smaller effects.

Proportional, progressive, and regressive

An important feature of tax systems is the percentage of the tax burden as it relates to income or consumption. The terms progressive, regressive, and proportional are used to describe the way the rate progresses from low to high, from high to low, or proportionally. The terms describe a distribution effect, which can be applied to any type of tax system (income or consumption) that meets the definition.

- A progressive tax is a tax imposed so that the effective tax rate increases as the amount to which the rate is applied increases.

- The opposite of a progressive tax is a regressive tax, where the effective tax rate decreases as the amount to which the rate is applied increases. This effect is commonly produced where means testing is used to withdraw tax allowances or state benefits, creating high marginal tax rates. The highest marginal tax rates are borne by those on the lowest incomes.

- In between is a proportional tax, where the effective tax rate is fixed, while the amount to which the rate is applied increases.

The terms can also be used to apply meaning to the taxation of select consumption, such as a tax on luxury goods and the exemption of basic necessities may be described as having progressive effects as it increases a tax burden on high end consumption and decreases a tax burden on low end consumption.

Direct and indirect

Main articles: Direct tax and Indirect tax

Taxes are sometimes referred to as "direct taxes" or "indirect taxes". The meaning of these terms can vary in different contexts, which can sometimes lead to confusion. An economic definition, by Atkinson, states that "...direct taxes may be adjusted to the individual characteristics of the taxpayer, whereas indirect taxes are levied on transactions irrespective of the circumstances of buyer or seller." (A. B. Atkinson, Optimal Taxation and the Direct Versus Indirect Tax Controversy, 10 Can. J. Econ. 590, 592 (1977)). According to this definition, for example, income tax is "direct", and sales tax is "indirect". In law, the terms may have different meanings. In U.S. constitutional law, for instance, direct taxes refer to poll taxes and property taxes, which are based on simple existence or ownership. Indirect taxes are imposed on events, rights, privileges, and activities. Thus, a tax on the sale of property would be considered an indirect tax, whereas the tax on simply owning the property itself would be a direct tax. The distinction between direct and indirect taxation can be subtle but can be important under the law.

Tax incidence

Law establishes from whom a tax is collected. In many countries, taxes are imposed on business (such as corporate taxes or portions of payroll taxes). However, who ultimately pays the tax (the tax "burden") is determined by the marketplace as taxes become embedded into production costs. Depending on how quantities supplied and demanded vary with price (the "elasticities" of supply and demand), a tax can be absorbed by the seller (in the form of lower pre-tax prices), or by the buyer (in the form of higher post-tax prices). If the elasticity of supply is low, more of the tax will be paid by the supplier. If the elasticity of demand is low, more will be paid by the customer; and, contrariwise for the cases where those elasticities are high. If the seller is a competitive firm, the tax burden is distributed over the factors of production depending on the elasticities thereof; this includes workers (in the form of lower wages), capital investors (in the form of loss to shareholders), landowners (in the form of lower rents), entrepreneurs (in the form of lower wages of superintendence) and customers (in the form of higher prices).

Law establishes from whom a tax is collected. In many countries, taxes are imposed on business (such as corporate taxes or portions of payroll taxes). However, who ultimately pays the tax (the tax "burden") is determined by the marketplace as taxes become embedded into production costs. Depending on how quantities supplied and demanded vary with price (the "elasticities" of supply and demand), a tax can be absorbed by the seller (in the form of lower pre-tax prices), or by the buyer (in the form of higher post-tax prices). If the elasticity of supply is low, more of the tax will be paid by the supplier. If the elasticity of demand is low, more will be paid by the customer; and, contrariwise for the cases where those elasticities are high. If the seller is a competitive firm, the tax burden is distributed over the factors of production depending on the elasticities thereof; this includes workers (in the form of lower wages), capital investors (in the form of loss to shareholders), landowners (in the form of lower rents), entrepreneurs (in the form of lower wages of superintendence) and customers (in the form of higher prices).The negative impact of a tax has two components, the increased prices and lower incomes described above which must be distinguished from the loss of "economic efficiency", these are illustrated in the attached figure.

To illustrate this relationship, suppose that the market price of a product is $1.00, and that a $0.50 tax is imposed on the product that, by law, is to be collected from the seller. If the product has an elastic demand, a greater portion of the tax will be absorbed by the seller. This is because goods with elastic demand cause a large decline in quantity demanded for a small increase in price. Therefore in order to stabilise sales, the seller absorbs more of the additional tax burden. For example, the seller might drop the price of the product to $0.70 so that, after adding in the tax, the buyer pays a total of $1.20, or $0.20 more than he did before the $0.50 tax was imposed. In this example, the buyer has paid $0.20 of the $0.50 tax (in the form of a post-tax price) and the seller has paid the remaining $0.30 (in the form of a lower pre-tax price).

Taxation levels

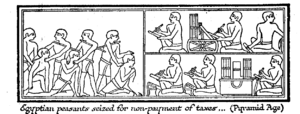

The first known system of taxation was in Ancient Egypt around 3000 BC - 2800 BC in the first dynasty of the Old Kingdom. Records from the time document that the pharaoh would conduct a biennial tour of the kingdom, collecting tax revenues from the people. Other records are granary receipts on limestone flakes and papyrus. Early taxation is also described in the Bible. In Genesis (chapter 47, verse 24 - the New International Version), it states "But when the crop comes in, give a fifth of it to Pharaoh. The other four-fifths you may keep as seed for the fields and as food for yourselves and your households and your children". Joseph was telling the people of Egypt how to divide their crop, providing a portion to the Pharaoh. A share (20%) of the crop was the tax.

Later, in the Persian Empire, a regulated and sustainable tax system was introduced by Darius I the Great in 500 BC;[11] the Persian system of taxation was tailored to each Satrapy (the area ruled by a Satrap or provincial governor). At differing times, there were between 20 and 30 Satrapies in the Empire and each was assessed according to its supposed productivity. It was the responsibility of the Satrap to collect the due amount and to send it to the emperor, after deducting his expenses (the expenses and the power of deciding precisely how and from whom to raise the money in the province, offer maximum opportunity for rich pickings). The quantities demanded from the various provinces gave a vivid picture of their economic potential. For instance, Babylon was assessed for the highest amount and for a startling mixture of commodities; 1,000 silver talents and four months supply of food for the army. India, a province fabled for its gold, was to supply gold dust equal in value to the very large amount of 4,680 silver talents. Egypt was known for the wealth of its crops; it was to be the granary of the Persian Empire (and, later, of the Roman Empire) and was required to provide 120,000 measures of grain in addition to 700 talents of silver. This was exclusively a tax levied on subject peoples. Persians and Medes paid no tax, but, they were liable at any time to serve in the army.

In India, Islamic rulers imposed jizya (a poll tax on non-Muslims) starting in the 11th century. It was abolished by Akbar.

Numerous records of government tax collection in Europe since at least the 17th century are still available today. But taxation levels are hard to compare to the size and flow of the economy since production numbers are not as readily available, however. Government expenditures and revenue in France during the 17th century went from about 24.30 million livres in 1600-10 to about 126.86 million livres in 1650-59 to about 117.99 million livres in 1700-10 when government debt had reached 1.6 billion livres. In 1780–89, it reached 421.50 million livres. Taxation as a percentage of production of final goods may have reached 15%–20% during the 17th century in places such as France, the Netherlands, and Scandinavia. During the war-filled years of the eighteenth and early nineteenth century, tax rates in Europe increased dramatically as war became more expensive and governments became more centralized and adept at gathering taxes. This increase was greatest in England, Peter Mathias and Patrick O'Brien found that the tax burden increased by 85% over this period. Another study confirmed this number, finding that per capita tax revenues had grown almost sixfold over the eighteenth century, but that steady economic growth had made the real burden on each individual only double over this period before the industrial revolution. Average tax rates were higher in Britain than France the years before the French Revolution, twice in per capita income comparison, but they were mostly placed on international trade. In France, taxes were lower but the burden was mainly on landowners, individuals, and internal trade and thus created far more resentment.

Taxation as a percentage of GDP in 2003 was 56.1% in Denmark, 54.5% in France, 49.0% in the Euro area, 42.6% in the United Kingdom, 35.7% in the United States, 35.2% in Ireland, and among all OECD members an average of 40.7%.

Forms of taxation

In monetary economies prior to fiat banking, a critical form of taxation was seigniorage, the tax on the creation of money.

Other obsolete forms of taxation include:

- Scutage, which is paid in lieu of military service; strictly speaking, it is a commutation of a non-tax obligation rather than a tax as such but functioning as a tax in practice.

- Tallage, a tax on feudal dependents.

- Tithe, a tax-like payment (one tenth of one's earnings or agricultural produce), paid to the Church (and thus too specific to be a tax in strict technical terms). This should not be confused with the modern practice of the same name which is normally voluntary.

- (Feudal) aids, a type of tax or due that was paid by a vassal to his lord during feudal times.

- Danegeld, a medieval land tax originally raised to pay off raiding Danes and later used to fund military expenditures.

- Carucage, a tax which replaced the danegeld in England.

- Tax farming, the principle of assigning the responsibility for tax revenue collection to private citizens or groups.

Some principalities taxed windows, doors, or cabinets to reduce consumption of imported glass and hardware. Armoires, hutches, and wardrobes were employed to evade taxes on doors and cabinets. In some circumstances, taxes are also used to enforce public policy like congestion charge (to cut road traffic and encourage public transport) in London. In Tsarist Russia, taxes were clamped on beards. Today, one of the most-complicated taxation systems worldwide is in Germany. Three quarters of the world's taxation literature refers to the German system.[citation needed] There are 118 laws, 185 forms, and 96,000 regulations, spending €3.7 billion to collect the income tax. Today, governments of advanced economies of E.U., North America, and others rely more on direct taxes, while those of developing economies of India, Africa, and others rely more on indirect taxes.

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar